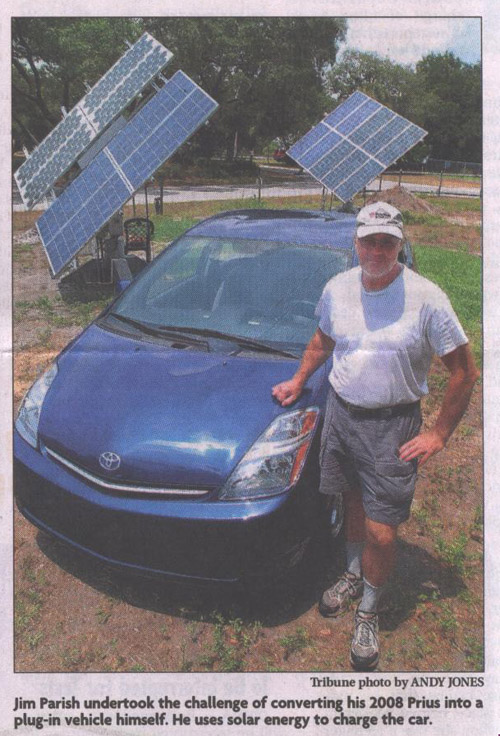

So, its not a secret that I think the prius is an overhyped ugly as sin car, but some people do some pretty interesting things with them. Wizbandit (Jim Parish), my solar leader, made the paper is his part of the world for his car.

Published: June 16, 2008

TAMPA – Jim Parish gets envious looks from drivers when his modified plug-in Toyota Prius cruises down the highway.

It’s easy to see why. A bumper sticker tells motorists: “This plug-in hybrid gets 100+ MPG.”

Strangers regularly ask Parish, a Tarpon Springs resident, how they can get one. He particularly likes cruising by gas stations where people are lined up to pay almost $4 a gallon for gas.

Electric vehicles are still enough of a novelty to draw double-takes on the road, but that might not be true for long. As fuel prices continue to soar, more people are exploring converting their cars to electric vehicles or hybrid-electric to avoid the pain at the pump.

Some, like Parish, do most of the work themselves, viewing the job as much a technical challenge as an ecostatement.

Others are turning to the handful of gas-to-electric conversion companies operating in Florida. Those companies are reporting significantly improved business during the past year, and national suppliers say they’re posting record sales the past few months.

Lithium battery seller LionEV Inc. of Chesapeake, Va., says orders have grown tenfold from six months ago. NetGain Motor Inc., an electric motor producer in Lockport, Ill., says sales the first five months of this year eclipsed last year’s total.

“The June build is sold out, and August is almost sold out,” said Les Heberer, sales manager at NetGain. “We get calls constantly.”

Parish converted his 2008 Prius after contacting a group in California that promotes plug-in hybrids.

He bought the car in September. After planning and gathering parts over a couple of months, he started tinkering with it on weekends in February.

The most visible results are inside the trunk, where 20 gray batteries take up most of the narrow space.

On the highway, Parish sees the fruit of his work. What was good mileage to begin with – 40 to 50 miles per gallon – now is an amazing 100 plus mpg.

Parish gasses up his plug-in hybrid twice monthly when the gauge falls to half a tank. On a full charge, the car runs electric-only the first 40 miles before automatically switching over to hybrid operation.

Shawn Waggoner, president of the Florida Electric Auto Association in Lake Worth, said purely electric cars and light trucks still number fewer than 100 in Florida, but demand is increasing with each uptick in gas prices.

Also helping: Major carmakers are considering a line of all-electric vehicles for launch in 2010 or 2011.

Steve Clunn, owner of Grassroots Electric Vehicles in Fort Pierce, said he’s fielding dozens of calls daily from gas-price-weary drivers. He quit his regular job running a lawn maintenance company to work at conversions full time.

“It’s incredibly busy,” he said.

Clunn performed three conversions last year. So far this year he’s done two and is working on three more.

The gas-to-electric business isn’t exactly speed-bump-free, though.

Conversions aren’t cheap, averaging $10,000 to $20,000 each, including labor. Parts alone can fetch $5,000 to $15,000, depending on the vehicle and type of batteries.

Standard lead-acid batteries are the favored choice based on price, but they’re heavy at 30 to 40 pounds each and need maintenance. Lithium batteries, the new gold standard in the electric vehicle market, solve that problem but cost much more. Outfitting a car with lithium batteries can run almost $10,000.

Of course, drivers must pay to charge their batteries – pennies on the dollar. The refrain among electric vehicle fans is that regular cars cost an average of 20 cents a mile, whereas electric ones cost 2 to 4 cents a mile.

“It’s like pre-paying for gas for five years,” Waggoner said.

There are other issues to consider with electric cars. A vehicle with lead-acid batteries runs 40 to 50 miles between charges, making them suited only for short trips.

Lithium batteries, however, expand that range to 175 to 200 miles. Another upside is they’re maintenance-free, last much longer and offer more power and better acceleration, said Ken Curry, an engineer at LionEV, which specializes in the high-tech batteries.

Lead-acid batteries can require topping off with distilled water and need to be changed out every five to 10 years.

Miami-based ProEV Inc. says electric cars are here to stay and that lithium batteries probably will take the industry mainstream.

“The price of batteries will come down,” said ProEv’s owner, Cliff Rassweiler.

ProEV builds high-performance cars using lithium-polymer batteries that can hit up to 160 mph. The company’s aim is to test and promote high-end electric vehicle technology.

At a constant 60 mph, ProEV’s cars can go 175 miles between charges, he said.

“That’s using the latest technology today. Nobody knows what the batteries will do in 10 years,” he said.

Tampa mechanic Jeff Dugliss also is sold on the potential of lithium batteries.

Dugliss co-owns Rennen Imports, an auto repair business on Kennedy Boulevard. He recently stripped down a 1972 MGB and ordered about $12,000 in parts, including two electric motors that will sit side-by-side under the hood.

“It’s nice and light now,” Dugliss, 32, said of the canary yellow sports car. “The lighter the weight, the less energy needed to push it.”

Dugliss plans to remove anything unnecessary, including the side windows and convertible top. He might even replace the steel rims with lightweight aluminum ones. The batteries will be dispersed evenly across the car to keep it balanced.

“This definitely is for driving on sunny days. If it rains, you get wet,” he said.

When finished, sometime this summer, Dugliss and his mechanics will take turns driving the car home.

“I don’t want to build a car that goes 5 miles an hour. I want this to be quick. I want to be able to do smoky doughnuts,” he said.

For other drivers, performance isn’t the main issue.

Cornelius Cronin of Oldsmar last year converted a 1994 Chevrolet S-10 pickup using lead-acid batteries. He admits the performance is sluggish starting from a dead stop, but the vehicle runs fine after that, he said.

“The acceleration is the same as a regular four-cylinder if you were carrying 1,600 pounds of batteries,” he said.

On the other hand, Cronin hasn’t paid for gas all year.

“Every two months I put a little distilled water in the batteries. That’s it.”